Queens Museum interviewed in New Series by Rehan Ansari and Brooklyn Rail

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, One Year’s Worktime II, (2016). Courtesy the Queens Museum. Courtesy Queens museum. Photo by Hai Zhang. [image description: in a massive foyer space, there is a curved wall in the background where there is a printed image, which from left to right changes color from green, blue, purple, red and finally orange]

Forecasting Art and Social Justice by Rehan Ansari

On February 8th Sara Reisman, George Bolster, and Rehan Ansari sat down with several members of the Queens Museum staff—Hitomi Iwasaki, Director of Exhibitions and Curator; Larissa Harris, Curator; and Prerana Reddy, Director of Public Programs and Community Engagement—to talk about their work and the museum’s role in the community.

Rehan Ansari (Rail): To start off, what are you not asked about these days?

Larissa Harris: I am surprised people don’t ask us how we are doing after the expansion. By “people” I mean professional colleagues. The renovation has had an effect on us. The change of scale has affected our capacity. Yet we’re also very much the same.

Prerana Reddy: We maintain the same community partnerships and are still open for collaboration and dialogue with the local community. The building, however, is now a challenge because it looks fancy and new. The previous layout of the museum looked more approachable. We have had to overcome the scale for our community audiences.

Sara Reisman: How does that change their experience? Is it still as accessible and familiar?

Reddy: We now have this huge open space in the middle. The actual exhibition space is hidden, even though it’s open. Because they’re linear and U-shaped, you have to choose to enter the galleries. So there’s this trade-off: we now have big public square that can host programming and function in a lot of ways and is also a free zone but it makes the exhibitions proper something you have to choose.

Hitomi Iwasaki: It is also an opportunity to create an interesting fusion space.

Reisman: Can you talk about the fact that the museum is considered to be the museum that does social practice even though it does so much else? Ten years ago you talked about the legacy of multiculturalism, which was about an even earlier era in the museum’s history. I am suggesting that there is a connection between that history—multiculturalism—and the current work with socially engaged art. Does the legacy of multiculturalism feel relevant right now?

Iwasaki: The transition came naturally to us. I joined the Museum in 1996 when it was churning out exhibitions like Out of India, Cai Guo-Qiang (1997), and preparing for Global Conceptualism (1999), the iconic period which I view in retrospect as marking the transition from multicultural to global as exhibition framework. The connection between that legacy and social practice now has to do with a larger mission of making art as an institutional practice accessible to larger audiences in a democracy. And that had to with us already having immense cultural diversity in our constituency, and the programming we already had in place.

Anna K.E., Profound Approach and Easy Outcome, 2017. (installation view). 140 ft. x 27 ft. Courtesy the artist. Photo by Hai Zhang. [image description: on huge curving wall in foyer space there are a number of images against the white wall, left, there is a woman holding something, with a portrait of a man behind her, In the middle there is a jigsaw like distortion of different colors, and on the right there is a woman looking in a mirror]

Harris: I think the three of us react in different ways to the needs of our location and our audience. When I came in 2009, I tried to understand what kind of art the place wanted. I believe it wants to host artworks that aren’t sealed hermetically, which have an element of play and invitation. That sensibility can underlie a lot of different kinds of work . . . the Anna K. E. installation (Profound Approach and Easy Outcome, 2017), for example, which was commissioned by Hitomi, has nothing to do with “social practice,” but it is incredibly inviting because of the way it seems to ask questions like, “What is a museum?,” “What do I do in a museum?” and suggests that actually it can be a place to play—to enjoy being who I am up against what the museum, or The Museum, may have to offer.

Iwasaki: I think that “social practice” is a catchphrase like previous ones—multiculturalism, globalism, etc.—that have eventually become part of their historical period. What’s important is rethinking the accessibility of art and what it means to be an institution that is a mediator, working to make the arts accessible. Strong art, a strong institution and strong curatorial practice should be able to handle this.

Reddy: Also what has happened is that the museum entered community spaces—the street, the plaza—in a consistent way, not because we were interested in social practice, but because we were interested in the museum in a local, social role, and expanding the sense of space. We wanted art that responded to stated community desires and highlighted community dynamics. That’s how our first public art projects in Corona Plaza emerged.

Reisman: Can you talk about how your engagement with Corona Plaza came about?

Reddy: It came about from the fact that we didn’t want to do just outreach, but actually wanted to be out there as part of the neighborhood ecology. We hired a community organizer in 2006, and then when we had the community organizer convene people, we heard a laundry list of needs and challenges. Some of them were beyond our capacity to affect change, like affordable housing, but we noticed that a lot of residents talked about the lack of public space and the lack of basic maintenance of public infrastructure. People in Corona thought that the city thought that the community was not worth investing in, and that the city blamed the community for the problems they were experiencing. These were the narratives that needed to be changed—among community members, city officials, and elected officials—and we thought that’s where an arts organization could involve itself. The same thing with health: we cannot change the health insurance system, but we can reconnect people to healthy practices and provide a space and a platform for nutritional education, physical activity, dance—cultural forms that are embedded with specific ethnic and local knowledges. The use of public space became a way to address these narratives and engage creative people in the design community, the urban planning community, and artists in the social practice community. We brought artists to do playful social research to reveal things below the surface that are not visible through business surveys and existing city data. I think that I wasn’t trying to look for social practice artists but artists that would bring these elements together and who would bring joy to these kinds of often moribund civic processes.

Reisman: I remember the three criteria for the artists in the 2008 project—I was curator of Center of Everywhere V2 at Corona Plaza—were that they be “socially engaged,” “community-based,” and “interactive.” What came before to set this in place?

Reddy: I started working at the Museum in 2004, and our department was being formed as “Public Events,” separate from the Education Department. It is called Public Programs and Community Engagement now. We spent all our time, Jaishri Abichandani and I, figuring out where people like us—immigrants who consider themselves artists and cultural producers—were and who would see the museum as an asset and a platform and start from there. We would go to organizers in the community and ask them, “Who is responsible for the social life in the community? Lets try and find these folks, and see if we give them the museum space and some resources, what they come up with and what they need.” So that’s how it started out—some things became independently-curated series, some became annual holiday or ritual celebrations, some became true collaborations with the museum staff. The partnership gallery was resurrected not just as a place for children’s artwork from the Education Department, but as a space for short exhibitions from our community partners. We also had a long term arts education program called Leadership Through the Arts, a year-long program for young people from Queens that combined political education, meeting community organizations and non-profits, and meeting with artists to develop work around social issues in various mediums in their own neighborhoods. I was hired initially to start that in 2004.

Pedro Lasch, Statements on Masks, 2005. Courtesy Queens museum. Photo by Hai Zhang. [image description: people on the left of the images watch a man on the right seated at a wooden desk holding up text, He is wearing a mirror mask with slits for eyes and mouth, he has a black rectangle behind him]

We began to see that people had an attachment to this space, that it wasn’t just an exhibition space. It became a making and learning space. When kids were here developing work with professional artists, interesting things began to happen. And sometimes the teaching artists in our program had exhibited at the Museum before, and were really excited to be part of this institutional change; folks like Pedro Lasch and Judith Sloan who already had collaborated with local youth helped advise the program. While this program was successful in that many of the participants went on to have good educational outcomes, became artists, or worked in cultural institutions, it was not able to sustain their work across multiple neighborhoods. So we had to become more focused geographically and that’s how we decided to work long-term in Corona. This is our neighborhood, we don’t have the human capacity to do something consistent in Jamaica which is quite hard to reach via public transport for example. But internally, it cracked the museum open to have all these young people here from all these backgrounds occupying space on a regular basis. .

Iwasaki: Then Queens Teens started. That’s nested in our Education department. It engages local high school students for a year-long program, they come once a week and sit down and do stuff with educators and with curators. They see what curators do when working with contemporary art—we give them in-depth access. They learn certain skills pertaining to the museum and participate in museum activities and become part of the museum mechanism and play their own role. It is a long-term commitment. They even come back sometimes and get to work here.

Reddy: Our program was about how people utilize art and culture to analyze and understand social issues and what are the skills involved in taking ideas to the public. They would get a relationship with professional artists.

Reisman: It sounds like a laboratory.

Rail: Do you feel you are figuring it out as it is happening?

Reddy: It’s a process of listening. Trying to match what we have as an institution—space, people, networks—with what our communities need, and their needs can be big: housing, health, educational, and legal. In 2011, we initiated Immigrant Movement International (IMI), a long term project based in a storefront space in Corona with Tania Bruguera. When she was ready to move on to do work in Cuba that was politically necessary and timely, and we felt we had to something with the community of folks who had utilized the space and for whom it had become important in their social life. Do we say “you have another three months and then we wrap up”? What responsibility do we have to a community that we had helped bring together? Not that I had an answer. Do we bring in another artist? Eventually, with Tania, we decided that the project become Immigrant Movement International - Corona. We created a community council, but how do we make decisions together? What kind of resources can we bring? Right now we are going through another phase of strategic planning: does IMI Corona become independent, a grassroots community organizing entity in the neighborhood? What relationship does it want with the museum moving forward? I don’t know if I want to tell people what it should be, if it’s truly a collaboration. Yes it’s an experiment, and we are stumbling into the questions that social practice engages in terms of length, relationship to community. Is it conceptual, or does it have real social effects? Is it symbolic, or is it not?… When working with Tania it became a genre of art called Arte Útil with certain intentions, but then what are the questions we are asking five years later? We didn’t declare ourselves to be a social practice institution, but our values and our partnerships have led us to a similar set of questions.

Rail: When does sanctuary spaces as a term come in?

Reddy: People already know what kind of spaces are physical sanctuaries, or not. There is a kind of symbolic sanctuary that we can talk about, that a museum is a kind of cultural sanctuary where all people are welcomed despite immigration status or identity, and different viewpoints are respected… I think for us it has meant that providing information and services, as well as creating opportunities for debate about the topic of immigration on a consistent basis is a big part of it.

Reisman: Museums in general or the Queens Museum?

Reddy: Any museum could be. I heard a talk about this in Ferguson that people were using museum spaces to convene and strategize, but when the police come, are you going to stop the police from entering the space and how? There are questions about power that have to be thought about seriously in terms of owning the term. That, and how you articulate the kind of sanctuary provided, is going to take a while to understand.

Reisman: You have long served immigrant communities surrounding the museum—that implicitly suggests a safer space. Has that changed in any way or does it continue as usual?

Reddy: There is no shift in our desire to be welcoming, open, and accessible. There is no dramatic shift in what we do in the neighborhood. What has been challenging at Immigrant Movement International Corona is how to engage the actual needs of folks, legal and psychological, that require networks less to do with art, and more to do with other kinds of immigrant-serving organizations. We have to be realistic about what we can provide and secure. There are limitations to sanctuary cities and it’s a changing legal environment. The city has a certain jurisdiction and so do we. This museum, because of what it offers as programming, makes it a sanctuary along the lines of a public library. The generations of teens and kids who now as adults find it welcoming makes this a sanctuary to an extent.

Reisman: How does it relate to exhibitions?

Harris: The next step would be to develop programming working with Prerana and her crew for the IMI cohort and other people in the neighborhood who may still not feel contemporary art is in their wheelhouse. Maybe figure out a special interface, a bridge for specific people who are already connected to QM through Corona programming but wouldn’t necessarily feel ownership at the QM “mothership.” Again, this is something we’ve tried out in various ways already.

Reddy: There is something about a feeling of safety and intimacy.

Bolster: A feeling of neighborhood and comfort?

Marinella Senatore, MétallOpérette, 2016, 4k video, stereo, color, sound, 25’. Courtesy the Queens Museum. Courtesy Queens museum. Photo by Hai Zhang. [image description: a geometric room like structure in wood with a neon sign in orange is in the foreground protest language is on the black back wall in blue]

Harris: It takes a long, long time to develop the relationships that Prerana and her team have developed. And those have been unfolding as a part of the Museum’s mission, but the fact remains that the Museum’s different departments do a lot of things separately.

Bolster: When we came to the opening for Marinella Senatore the level of activation of the local community for a project like that was stunning. It doesn’t exist in Manhattan. It was very inspiring to come here.

Harris: The participants in the Marinella Senatore performance actually came from all over New York—Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan (unfortunately I don’t think we had Staten Island participants). Our new assistant curator for public programs, the amazing Lindsey Berfond, worked on recruitment and choreography with Marinella. It did involve a few already-existing neighborhood partners, Corona Youth Music Project among them.

As for Tom [Finkelpearl], not only is he the one who laid out the framework for an open museum, he supported all of us over the years as we serially experimented with artists, mediums, duration, institution, partnerships, and audience/participants both inside and outside the museum.

Bolster: Did he start the job thinking that this is the people’s museum?

Harris: Tom is a unique combination of the creative/philosophical and the pragmatic. Of course I wasn’t there, but my sense is on being hired in 2002, he said to himself simultaneously “Why does this place exist? Who should it exist for?” and “Hmm, not many people from the neighborhood—or indeed from elsewhere—are in this museum. How can we justify its existence?” His professional experience includes both P.S.1 and Percent for Art—he was a perfect merger of insider and outsider. And then he hired Prerana.

Reddy: Jaishri was the first hire. She grew up in Corona, started SAWCC, was motivated by her art practice and the creation of community. If you can’t get that person to think the museum is for her, then how will you get someone else through the door? When we were hired we couldn’t believe we were in.

Rail: I am hearing lots of goals and processes leading to future goals. Do you have a mechanism to rank your goals against each other? Any thinking around these lines?

Iwasaki: As I was listening to Prerana I thought, “we have a body of people who don’t get a chance to mingle.” Putting new people between curatorial and public events is one way to make building exhibitions more organic, collaborative, and cross-pollinating. We have tried this before in different ways, and we will keep trying. We hope to become one integrated, organic team—we are not there yet. And we don’t have mechanisms to evaluate each other so far.

Reddy: Evaluation is hard. It has not been an institution-wide exercise. All of our programs do have indicators and evaluations. For example, in my department the community-based stuff has social indicators of change that we are trying to see, how do we know what kind of observations we need to be making, but it is quite anecdotal. We have an outside evaluator, but it’s someone who collaborated with us for two years, so they have a deeper sense of what we are trying to accomplish and a sensitivity to how to communicate to our community partners and participants. Unlike a program that has a discrete beginning and end, a certain number of sessions perhaps, what we are doing in my department can go on for seven or more years! How do we break up these long-term processes into phases we can evaluate? This year we are focusing on a strategic planning process at IMICorona for example. Our indicators are for people who volunteer and go through a facilitated process. Do they have a greater understanding of non-profit funding options? Are they better at expressing the vision of their organization in public? That’s what I am evaluating. It is hard to imagine this fitting into an institution-wide mechanism. We would appreciate insight and help on this.

Rail: We developed metrics workshops for arts organizations funded by the Shelly and Donald Rubin Foundation (SDRF). We created an index for SDRF by which they can measure their goals in a fast-moving dynamic environment.

Iwasaki: As much as I go against translating everything into numbers, sometimes seeing something like that helps.

Bolster: Can you tell us more about how you support under-recognized artistic practices?

Harris: In terms of supporting emerging artists, we started a residency program in 2013 with the expansion. It’s eight studios with an open call process and a selection jury of professionals, for a period of one year. We’re changing this to a two-year term in 2018.

Iwasaki: It’s $250/ month for a massive space.

Bolster: Does it bring a different sensibility to the museum?

Iwasaki: Yes. It makes the museum not just a place of presentation. You can also produce here.

Reddy: It’s a challenge because the first thing a studio program should do is have artists get to know each other. We organize studio visits, and there’s a small amount of money if you want to propose a public program. However, people in NYC are busy and don’t all use the space at the same time. Some cohorts come to our public programming all the time, others don’t. Being part of the residency at the Queens Museum perhaps does have an impact, for example someone like Onyedike Chuke who came here in the first residency cohort and now is part of the City’s PAIR Program at Rikers. It is not like he did coursework at Queens Museum in social practice, but perhaps there’s a chance he absorbed something from the environment here. Hard to measure, but I think if you are here enough, have enough conversations with staff, or interact with Museum’s visitors or programs, it could impact one’s art-making practice.

Rail: Take credit. That’s important in metrics. [Laughter]

Reddy: He left a couple of years ago—for how long does one take credit?! [Laughter]

Bolster: How does Social Practice Queens link to you?

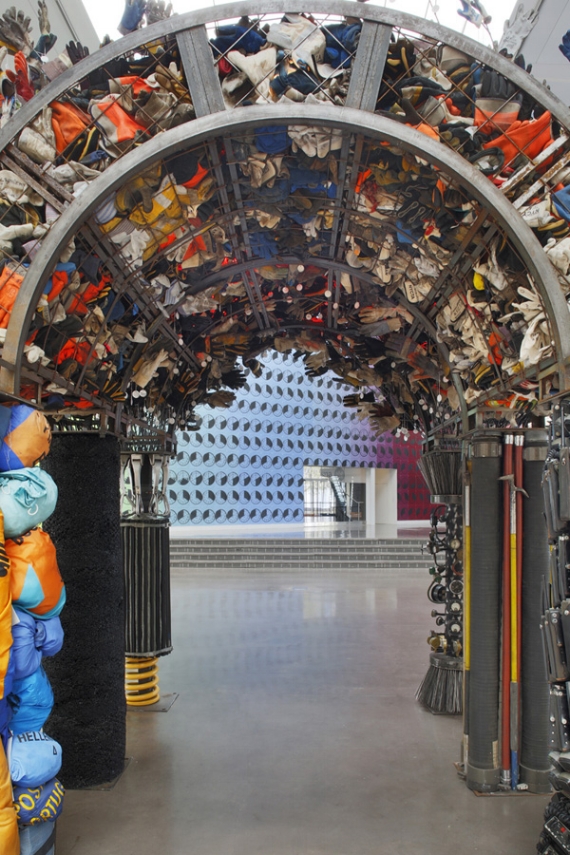

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Ceremonial Arch (1988/1994/2016) Courtesy Queens museum. Photo by Hai Zhang. [image description: a sculpture of an arch is in the foreground, it is made of different cleaning materials in a variety of colors, the objects include gloves, mops, mop handles. the background has a large colorful print on the wall, predominantly in blue and purple]

Harris: It even got some funding from SDRF.

George and Rehan: Thank you very much.

* Forecasting Art and Social Justice is an interview series sponsored by The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation to feature institutions and individuals whose work centers on art and social justice.

CONTRIBUTOR

REHAN ANSARI is a Brooklyn-based writer, playwright, and artist who also works as a political pollster and measures impact in the field of art and social justice. He recently performed political standup for Martha Wilson’s Activist History Teach-in at The 8th Floor in New York and for Little Injustice at Galéria HIT in Bratslava, Slovakia. His video Radical Contingencies was part of Crossing The Line at the Queens Museum, Summer 2001.